I. The APRON is the inside part of the keel. It is where the deadwood and ballast keel hang out together. It is made on a mold that gives it its shape. Several sheets of eight foot 3/4" plywood are scraphed end to end giving the needed length. This is sawed into six layers about a foot wide. After the mold is prepared for use the strips of plywood are laid on the mold, gluing as the layers are added. No glue is put on the first layer put on the mold in the area of the engine room. This unglued section (of what is the top layer after the backbone is set up on the building car) is cut out (after the backbone is finished) to allow the fiberglass pan to be positioned beneath the engine (this catches oil drippings to keep oil out of the bilge). A total of six layers makes up the apron. After the glue sets up the sides are cleared of all glue and sanded or scraped to new wood. The bevel on the bottom (or on the top when on the mold) is marked off and planed down, and the frames stations are marked on the sides. The ends are sawn to their marks to finish the job to the proper length. The after end is cut to the angle needed to match the set of the transom and the forward end is cut to various angles to match the apron to the forefoot, leaving a nib the width of the forefoot to receive frame 7. The apron is moved from the mold to the backbone assembly horses so the deadwood can be added.

|

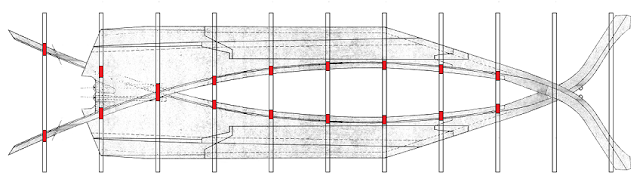

| Diagram of the Backbone Assembly Horses No scale |

II. The DEADWOOD,

along with deadeyes and deadweight, is called "dead" because it just

sits there. The purpose of the deadwood is to add to the

leeway resistance and is sized in the design process to locate the center of lateral resistance in the right place. On most, or many, boats the deadwood is located between the keel

and the horn timber. On the Newporter it is in two sections and is

between the keel and horn timber (the apron) and under the keel.

Construction fir is used in its construction. A layer

of 3/4" marine grade plywood is glued and mechanically fastened to each

side of the deadwood and keel. Note that the keel, also of fir, extends

from the forefoot to the after end of the deadwood. The upper two pieces

of the deadwood acts as the shaft log and are joined at the plane of the

centerline of the shaft. Prior to being put in the deadwood the lower

surface of the upper piece and the upper surface of the lower piece are passed across

a shaper to make half round coves that when the pieces are glued

together form the place for the shaft alley to be set. This is of smaller

inside diameter than is needed for the alley but will be relieved later in the

process. The stack of deadwood is glued and clamped together with the

keel at the appropriate level. The after

end is tapered to designed shape fore (somewhat ahead of after end) to aft and

top to bottom. It is then routed out for

Allthread bolts (unheaded bolts threaded end to end) with a core box cutter. The slots are just deep

enough for the full diameter of the Allthread to sit under but flush with the

surface. The plywood layers close the slots over making them bolt holes for the Allthread. The top of the deadwood is

dressed to match the bottom of the apron and the two are brought together and

clamped. The Allthread bolt holes are

reamed out with a long drill bit all the way through the apron. Then the two are

separated, glued and reassembled. The Allthread

has nuts and washers put on both ends and the bottom end of the bolt is peened over to prevent the nut from unscrewing. The upper nuts are tightened and here used as clamps. Other clamps are added along the

length of the apron and spikes are added in way of the keel where there is no deadwood. Either before or

after this glueup (there was a standard but it escapes me now) the forefoot and stem assembly is added to the apron/deadwood

unit. The keelbolts, that pierce the apron, keel and ballast, are

the main fasteners on this section, but this is done in the building shed after the foregoing

because the lead ballast keel (6000 pounds plus) is in the Building Shed where the boats are

built.

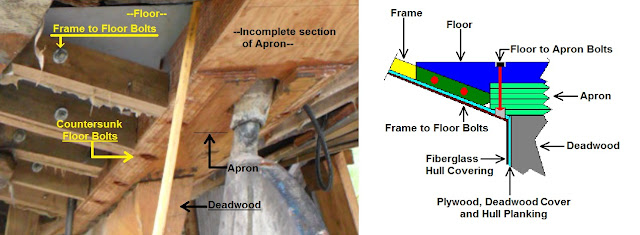

III. Illustrations of Deadwood Area Construction

The apron is one of the largest pieces in the Newporter. This should be, because it has a heavy responsibility. A study of the pictures above will show a lot of the construction of the hull. The frames are an assembly of the deck beams, topside frame and bottom frame pieces joined at the chine with knee and gusset combos, and the floor that joins the two bottom frames members. The floors of a Newporter (with frame attached) are notched over the apron (which is well attached to the deadwood, keel, and ballast, thus becoming a major part of the backbone) and well bolted to it. It was at this stage of building the hull when the shape of the finished boat is first seen. And so, it is the apron that marries the keel to the frames, and thus the hull. The apron also provides a good means of joining the bottom planking to the backbone.

IV. From Backbone to The Hull: A couple of hundred feet doesn't sound like much but the backbone had to be wheeled that far out of the "lean-to" where it was made, around the west end of the Quonset hut, through the alleyway between the joiner shop and the electric shop and into the building shed. A building car is assembled on the railway and its wheels chocked to prevent its movement. The backbone is then laid on its side and blocked up level port to starboard and clamped. The lead ballast keel is raised to the car and slid in place. The two are brought into alignment and clamped together for the drilling of the ballast bolts. These holes go up through the lead, wood keel, and the apron. Since I worked in the Quonset hut and the rigging loft I didn't get into this part of the construction, but (and here for a while experience will give way to supposition) there must be a bedding compound between the lead and the wood. This would fill the probable gaps left even after a careful leveling of the ballast top. After the ballast keel bolts are made up tight and the side of the lead that is up is dressed smooth the bottom of the keel is jacked up as high as it will go, setting that edge high and the apron side down. The bottom of the backbone is dressed smooth, ninety degree edges rounded off in best "fiberglass tradition," and the fiberglass is applied leaving a thick heavy application of fiberglass on the bottom and up the sides about six inches. The bottom is also painted to its finish coat (in that day, copper paint). After it is all dry the backbone, now including the ballast, is set up and plumbed to vertical and braced so the hull can be built on the set of wheels that will deliver her to the water.

After this intermediate step we can go to The Hull.